Why humans should worry about robo-advisors

Part 3: Millennials love automated advice, so traditional wealth managers must react to robots’ gains

- |

- Written by Paul Schaus

This is the third in a four-part viewpoints series by CCG Catalyst's Paul Schaus regarding banks versus fintech players.

This is the third in a four-part viewpoints series by CCG Catalyst's Paul Schaus regarding banks versus fintech players.

One of the biggest tailwinds behind the new entrants in financial services is the coming of age of millennials.

Financial services providers spent decades making their product and service portfolios more complex before the financial crisis forced them to rationalize their convoluted offerings.

Millennials are highly suspicious of the legacy complex products and services, having grown up during the Great Recession, and graduating from college loaded with student debt.

Few areas of financial services have proven as complex for them as wealth management services, where providers typically offer vast array of products with complicated and opaque fee structures.

Out in the weeds, a revolution

That complexity makes the current business model of established wealth management providers ripe for disruption. New entrants like Betterment, WealthFront, and FutureAdvisor are lining up to take advantage.

These new providers—much like the new competition in payments and lending—are using technology to offer services and acquire customers more cheaply while providing a digital-first customer experience that fits the needs—and frequently the preferences—of millennial consumers.

Rather than financing an office full of wealth management advisors to handle clients’ needs, these providers use algorithms to automatically invest their customers’ assets and adjust their portfolios according to their personal preferences.

These automated advisor services have been successful in targeting millennials, who established providers are overlooking in favor of older customers with more assets to invest.

[Editor’s note: How often have you heard a fellow banker say, “Millennials don’t have any money!!”—or said it yourself?]

Some numbers show the potential: WealthFront has more than 21,000 accounts, and 60% of its clients are under the age of 35; and 75% of Betterment’s 63,000-plus customers are under the age of 50.

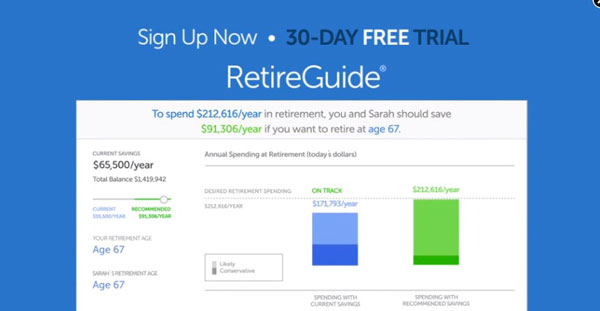

Betterment offers newcomers the ability to project savings versus future spending.

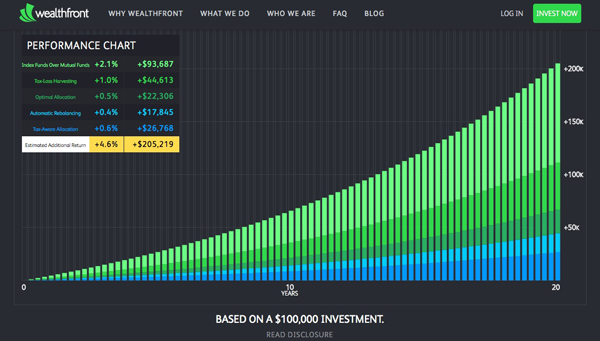

Wealthfront makes a projection to show millennials and others the possibilities.

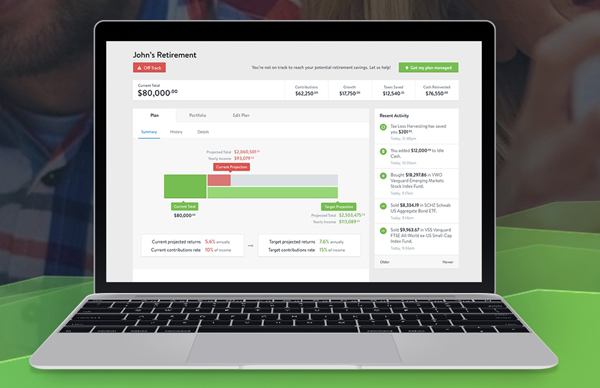

FutureAdvisor's site, like other fintech entrants, features attractive, interactive graphics.

Lower fees a must for millennials

Without an office full of human advisors to support, these automated advisor services also have much cheaper and simpler fee structures.

Consider this: Millennials are used to free financial services and products, as they’ve grown up with free checking and savings accounts.

Now grown up, when they go to invest some money with a traditional wealth advisor, that advisor usually charges a fee of one percent of their managed assets on top of the fees charged by the funds they invest in.

For comparison’s sake, the new service providers have a cheaper and simpler fee structure, as they typically only offer a single product. Betterment charges a fee of 0.15-0.35% of managed assets, and WealthFront charges 0.25%—and charges nothing for the first $10,000 of assets under management.

Millennials boost new players, traditionals fight back

So, there’s low costs. And there are great digital experiences—WealthFront and Betterment both have highly-rated iPhone apps. So it’s no wonder that these new entrants are growing fast with underserved millennial customers.

Earlier this year, A.T. Kearney projected that assets under management at these “robo advisor” firms would grow 68% annually over the next five years to reach $2.2 trillion in 2020. A.T. Kearney also said that about half of that value would come from assets already invested. So not only will these new players grow fast, they also will do so at the expense of traditional providers.

Those traditional players have responded by launching their own automated advisor services to compete with the likes of Betterment and WealthFront.

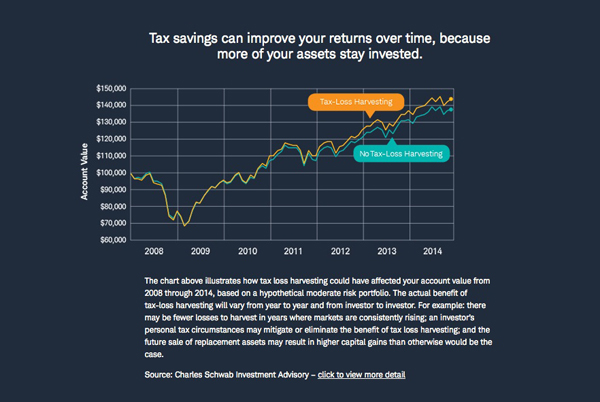

For example, Charles Schwab, one of the largest incumbents in the market with more than $2 trillion in assets under management, introduced the Schwab Intelligent Portfolios automated advisor service earlier this year. Customers need to invest a minimum of $5,000 to open a Schwab Intelligent Portfolios account, and Schwab charges no advisory fees, although it can recommend Schwab’s own investment funds, for which it charges management fees. Investment recommendations are made through an algorithm, although account holders can also talk with live advisors via phone.

Other incumbents should watch Schwab’s effort closely. The robo advisor market has low barriers to entry, making it easy for other wealth management providers to follow its example and offer their own robo advisor alternatives.

Schwab has a great deal to gain in the long term if it can attract younger customers with this new offering and then upsell them to products with a higher service levels and higher fees over time.

Charles Schwab's Schwab Intelligent Portfolios is among traditionalists' comebacks to the fintech movement's offerings.

Technology and trust: Can you beat the fintech folk?

Whether Schwab and other incumbents can compete with the new players will depend on two things:

• Can traditional players create competitive online and mobile user experiences?

• And will millennials trust the new players with their money over traditional investment advisors?

The new entrants have a definite advantage in their ability to offer enticing digital user experiences.

Unlike older providers, they’re not burdened with complex IT environments that make launching new digital products and services more costly and time-consuming. As other industries raise consumer expectations for digital experiences, the new players will be better prepared to meet those changing expectations.

Traditional players who overcome this challenge to offer automated advisor services with competitive digital experiences will still have to reckon with the issue of trust, as the new entrants will hold the short-term advantage there as well.

Consider some salient facts:

• A survey of millennials with at least $3 million in assets released earlier this year by Bank of America found that 53% of them do not use a financial advisor.

• New entrants’ algorithms (and Schwab’s as well) are largely based on how risk-averse a customer might be.

The latter is very important for millennials, as they tend to be very conservative with their money, given their need to repay student debt. Putting the issue of risk front-and-center gives the impression that the provider understands the needs of the millennial customer seeking to invest with as little peril as possible.

Ultimate proof: competition through all cycles

Over the long term, these new entrants will have to prove their customers’ trust through market downturns. Some of these new players will be able to protect their customers’ money during those downturns better than others. The same will be true among traditional providers.

Those players—both old and new—that are able to weather the storms better than others will be the ones who keep their customers’ trust over the long term, and build their customer relationships.

In a market worth trillions, the industry is big enough for both old and new players who accomplish that to find a place in it.

Just how much business new fintech entrants wind up taking away from incumbents will depend on how quickly traditional providers can launch competitive online and mobile automated services.

To read part 1 of this series, “Who will consumers choose?,” click here

To read part 2, “Fintech’s wallets don’t pay, for banks,” click here

Tagged under Management, Lines of Business, Retail Banking, Customers, Feature, Feature3,

Related items

- Inflation Continues to Grow Impacting All Parts of the Economy

- Banking Exchange Hosts Expert on Lending Regulatory Compliance

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- FinCEN Underestimates Time Required to File Suspicious Activity Report

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples