Could drought scorch California banks?

SNL Report: Four years in, bankers’ concern grows

- |

- Written by SNL Financial

By Kevin Dobbs, SNL Financial staff writer

The entrenched drought that canvasses California's rich agricultural region shows few signs of receding. Four years of elevated heat and too little precipitation during the winter months—normally a vital source of snow that melts in the spring and fills reservoirs in the state—has left water supplies low and many farmers scaling back.

The result: More farmers are fallowing crop land, and as this happens, they are spending less on fertilizer and myriad other supplies that go into producing food, worrying a range of small and midsize businesses that cater to or feed off of agricultural activity—including banks.

Not panicking, yet

Bankers say they are not panicking—the farm sector overall remains strong—but should the drought drag on another year or two, challenges could deepen enough to cause credit quality issues and other problems.

"I don't think we are alarmed or shocked, but we are watching it closely," Christopher Myers, president and CEO of Ontario, Calif.-based CVB Financial Corp., told SNL. "We are certainly concerned about the potential impact of the drought."

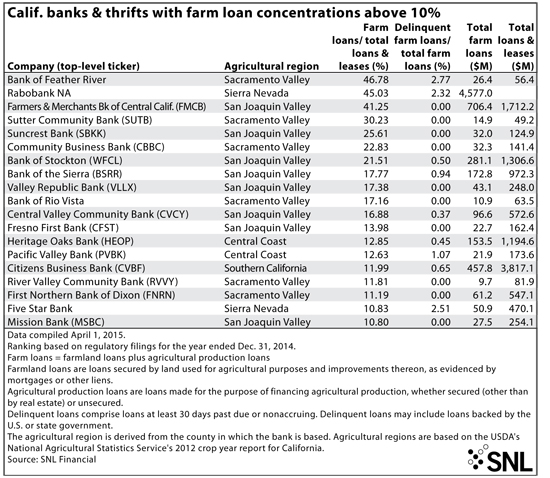

CVB Financial's Citizens Business Bank, like most notable California agriculture lenders, has a favorable credit profile and low levels of delinquent farm loans—less than 1% in Citizens' case, according to SNL data. This reflects the fact that American farms have benefited handsomely in recent years from rising global food demand, analysts say, making farmers and agribusinesses consistently profitable and equipping them with the financial wherewithal to absorb higher water costs or temporarily lower income from unplanted crop land.

"Ag has been strong, that's true," Darin Newsom, an agriculture analyst for Schneider Electric DTN, told SNL. But, he added, if the drought persists, water shortages could curtail enough production of vegetables, fruit, nuts, and dairy in California to significantly impact farmers and the economy of the state's ag-dominated Central Valley. Farmers' and ag-related businesses' ability to pay down loans could diminish greatly.

Already, Newsom said, high water costs and the quantity of fallowed land are both likely to increase this year. Much of California enters a dry season in the spring that typically extends until October, he said, and forecasts for precipitation next fall and winter are too long-range for Californians to rely upon, meaning nobody knows how long the drought will last. "It's all going to be cutting into bottom lines," Newsom said. "It's going to be a difficult year" for some California farmers, "and if this doesn't let up, it will get worse" in coming years.

Consumer impact far beyond California

Concern is running high not only because of the impact on California, Newsom said, but also because it could eventually result in higher food costs for consumers across the country.

California is the nation's most productive agriculture state, he said, and while farmers in other states can, for stretches, ramp up production of certain crops when California slows down, they cannot indefinitely replace what is normally generated in the Golden State.

Beyond potential credit quality issues, Newsom said, prolonged drought would result in less investment and therefore less loan demand from farmers. Festering uncertainty on these fronts is bound to make banks leery of inking long-term loan deals with farm operations, he said.

"So some banks are obviously nervous," he said.

CVB Financial's Myers stops short of describing himself as nervous. He says that, in addition to traditional crop-related loans, the company is more heavily involved in dairy industry lending—for herds and for land—and solid prices for milk have bolstered the standings of the vast majority of his bank's dairy customers. These farmers have put excess cash into digging deeper beneath their land for water, staving off the effects of drought, and many also have built up capital reserves to ride out the dry spell so far. Crop farmers, too, have taken steps such as planting more vegetables or fruits that require less water, he said.

Eye on farm customers’ access to water

But, Myers said, nobody at his bank is taking anything for granted. The drought is a serious matter, he said, and that is why the bank routinely evaluates its farm customers' planned future access to water. These annual appraisals—or more often in some cases—are done to help guard the bank against risky loans.

"If it looks like they might have a problem, we watch it closely," Myers said.

John DiMichele, vice-chairman and CEO of West Sacramento, Calif.-based Community Business Bank, paints a similar picture.

He said the vast majority of his bank's agriculture business is around or north of Stockton, Calif. South of Stockton, he said, banks already are finding major conflicts over access to dwindling water. Farther north, however, he said many of the crop farmers with whom his bank works still have reliable access to water—in one case, for instance, via a large lake.

"There is concern," DiMichele told SNL, "but it's not critical at this point for us."

Community Business Bank has no delinquent farm loans, according to SNL data. The bank also routinely examines customers' access to water.

But aside from sporadic storms, DiMichele said, "It's been a very dry winter and spring for us." If the drought persists into 2016 and beyond, he said, almost all Californians likely will experience its negative effects.

Among a plethora of downsides, cities would lose necessary access to water; housing construction could dry up if running water to new developments is not feasible; wildlife could get parched; recreation opportunities would fade; and of course food costs would climb, offsetting, at least in part, the benefits of lower gasoline prices that consumers have enjoyed since last summer.

"It would create a lot of issues, not only for our farmers but for everybody," DiMichele said.

Direct and indirect costs to agriculture alone could approach $3 billion this year, according to early estimates from the University of California, Davis. That would top the estimated loss of $2.2 billion in 2014—driven in large part by thousands of lost agriculture jobs—that researchers at the university estimated in a study last year.

As the drought continues, its effects deepen, that study concluded. It leads to "additional overdraft of aquifers and lower groundwater levels, thereby escalating pumping costs, land subsidence and drying up of wells."

It is, as DTN's Newsom summarized, "very serious."