Can address stability predict credit risk?

Viewed in proper context, data regarding moving can be indicative

- |

- Written by Ryan James Boyle, Trans Union

For a lender, how many moves are too many? TransUnion research scopes out some answers.

For a lender, how many moves are too many? TransUnion research scopes out some answers.

Moving residences is an inevitable life event. Everyone does it sooner or later, some more than others. The move can be exciting news: relocating for a new job, buying a first home, retiring to a warmer climate. It can be a bad circumstance: divorce, foreclosure, eviction.

Whatever causes us to pack up, we know it will disrupt our daily lives while we leave one location and get settled in another.

Can moving itself—and how frequently and how far someone moves—be an indicator of credit risk?

What does moving say?

One could argue that consumers who do not move for a long period of time are the ones who have their “houses in order,” both physically and financially. Consumers who move frequently may be relocating under duress. Conversely, they may be moving to take advantage of positive job opportunities.

We rarely know the reason for a move from credit data alone. However, data on the timing, frequency, and location of moves are available on the credit report when lenders report consumers’ new addresses.

TransUnion investigated whether changing addresses is a signal of changes in risk—positive or negative. We sought to answer whether lenders can gain any insight into a consumer’s risk by simply observing the number of recent addresses the consumer has on file.

We began with a review of consumers by the number of addresses they have on file. TransUnion maintains all addresses reported to us going back several years. We looked at all consumers who opened a new general-purpose bankcard in October-December 2013, and followed the performance of those new cards over the subsequent two years.

Taking a first look

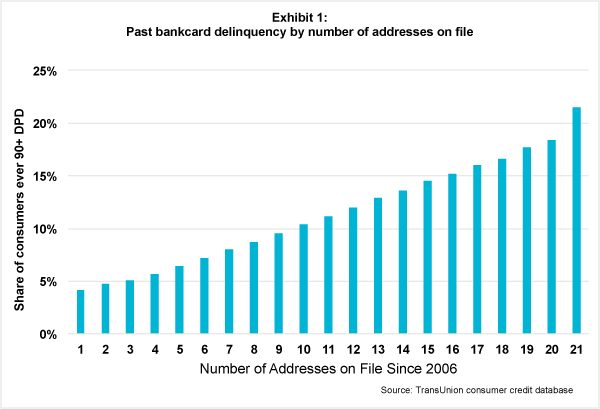

First, a simple review of addresses on file at the time of card origination shows the correlation between moving and risk.

Exhibit 1 looks at consumers with a credit card as of October 2013 and examines whether they had ever had a serious delinquency—that is, 90 days past due or worse—over the prior seven years. It also shows the number of addresses reported on their credit file over the same seven-year period.

We found that each additional address shows a marginally greater likelihood of a consumer having had a severe delinquency on an existing bankcard.

In fact, consumers with ten or more addresses on file are more than twice as likely to have been severely delinquent on a credit card than consumers with three or fewer prior addresses on file.

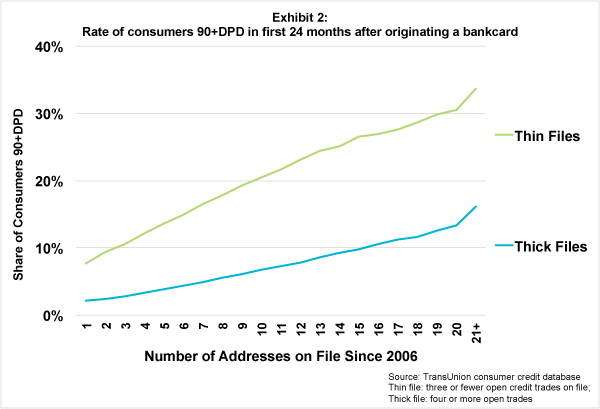

The performance on new accounts bears out the risk that the address history suggested.

Through thick and thin

In Exhibit 2, we follow the performance of bankcards opened in fourth quarter 2013 over the subsequent two years. We tracked, on an account level, how many of these cards ever had a 90-day or worse delinquency.

In this exhibit, we separate thin- and thick-file consumers, with thin-files defined as those having three or fewer existing credit accounts on file at the time of the new card origination. We see that address stability is a useful risk metric for both categories of consumers. However, stability proves especially helpful for rank-ordering the risk of thin-file consumers, who are more difficult to accurately assess using traditional risk-scoring tools.

One could argue that younger consumers may tend to relocate more often—the college student who moves with every new school year comes to mind. Past TransUnion research has demonstrated that younger consumers tend to have lower credit scores.

It is possible, one could argue, that the risk differences we see are driven by credit score differences (due to age differences) and are not a new insight.

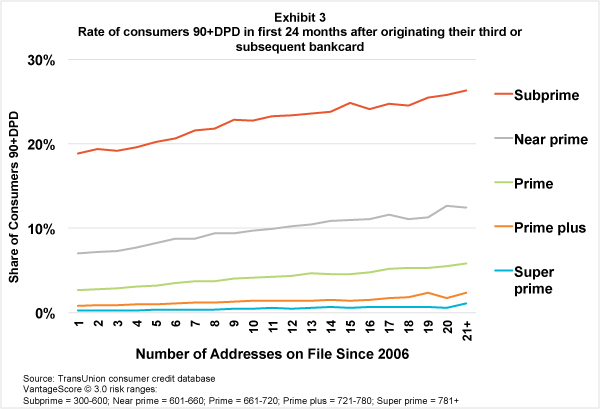

We therefore controlled our analysis for risk score differences, looking specifically at consumers with well-established credit profiles, and found our insights still held, as shown in Exhibit 3.

This is good news, as it means we’ve found an insight not explained by existing, traditional risk metrics.

What about the “good move”?

Of course, not all moves are equal. For instance, relocating for a new job is great news: if nothing else, it indicates the person is employed.

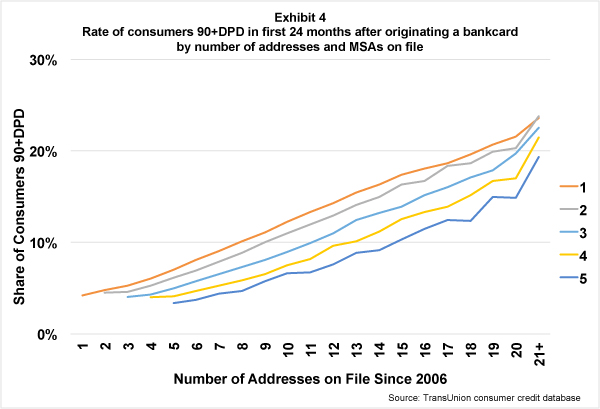

To control for these potentially positive circumstances, we separated consumers by the number of metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in which they lived. MSAs describe broad geographic areas; consumers are unlikely to move across MSAs regularly without the context of a significant life event.

As shown in Exhibit 4, we see that consumers whose moves have taken them to multiple MSAs—for example, Boston to Dallas—are significantly less risky than those whose moves have all been within one MSA.

Indeed, a consumer who has lived in five addresses across five MSAs appears to present even less credit risk than a consumer who has only one address on file.

A key benefit of this risk metric is that it requires only a database of “header” data—the consumer’s identifying information. No further detail is required about the consumer’s debts, historical loan performance, or credit inquiries. (TransUnion incorporates this metric as one component of our CreditVision® LinkSM risk score that blends traditional credit data and non-traditional “alternative” data.)

In the absence of conventional credit data, the number of recent addresses on file has proven to be a useful measure of a consumer’s credit risk.

A good tool to be used cautiously

A lender who chooses to use this insight for credit risk evaluation or to incorporate this metric into a credit score should be mindful of any appearance of redlining—that is, profiling a consumer based on prohibited characteristics, or even a disparate impact to protected classes based on an otherwise innocuous-seeming characteristic.

This risk metric is strictly a measure of how frequently and how far a person moves, and does not take current or prior zip code or neighborhood into account.

In this way, it does not consider whether a consumer currently lives or has previously lived in more or less affluent neighborhoods, and is a relevant metric regardless of where the person has lived.

Lenders should ensure they have policies in force to apply this metric to all consumer demographics.

Similarly, lenders should apply caution when using this metric to assess consumers who are active-duty members of the armed forces, or who have known military addresses in their address history. Because their duties often require frequent address changes, lenders need to ensure that members of the military are not penalized in credit decisions for this aspect of their duty.

Address stability is one of a growing number of ways that lenders can look beyond conventional credit performance data to assess risk and extend credit to consumers with limited credit histories. It is yet one more emerging trend that will allow for greater consumer participation in the lending market by helping lenders make more-informed risk decisions.

About the author

Ryan James Boyle is a senior manager of the Financial Services Research and Consulting team at TransUnion. He can be reached at [email protected].

Tagged under Consumer Credit, Risk Management, Credit Risk, Mortgage/CRE, Residential, Feature, Feature3,

Related items

- Inflation Continues to Grow Impacting All Parts of the Economy

- Banking Exchange Hosts Expert on Lending Regulatory Compliance

- Merger & Acquisition Round Up: MidFirst Bank, Provident

- FinCEN Underestimates Time Required to File Suspicious Activity Report

- Retirement Planning Creates Discord Among Couples