Employee turnover: Dealing with costs seen and hidden

Major turnover hits both officer and nonofficer ranks

- |

- Written by Crowe Compensation Survey 2017

Second of a series: Crowe Horwath LLP consultants discuss survey findings dealing with turnover issues. Then they explore potential solutions banks can try.

Second of a series: Crowe Horwath LLP consultants discuss survey findings dealing with turnover issues. Then they explore potential solutions banks can try.

With employee turnover rates in the banking industry at a ten-year high, banks must recognize the true costs of turnover, understand the underlying causes, and develop strategies to address the causes.

People still matter

No matter how advanced banking technology becomes in the coming years, motivated and talented employees will continue to play a critical role in any banking organization’s success. New research shows that the competition for productive, high-performing employees has increased significantly over the past few years, with no signs of slowing down anytime soon. [See part one of this series, “Talent competition: missed opportunities as competition intensifies”]

Clear evidence of the intensifying competition for talent can be seen in trends that have been recorded over the past several years in the Crowe Horwath LLP Financial Institutions Compensation and Benefits Survey. Of the many compensation and human resource measures that are tracked in this annual survey, one measure in particular stood out in the 2016 responses.

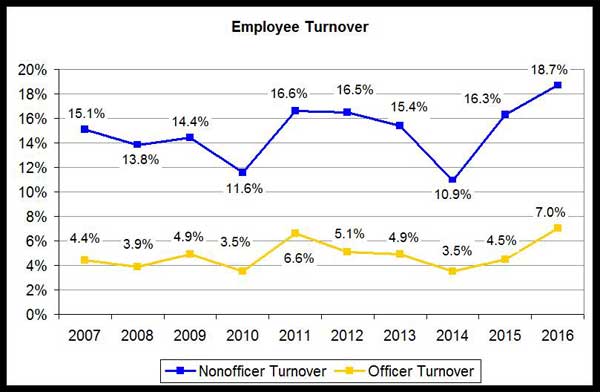

The survey shows that employees are changing jobs at a faster pace, with turnover rates reaching a decade high in 2016. As Exhibit 1 illustrates, turnover rates for both officer and nonofficer positions have trended sharply upward over the past two years and have now passed prerecession levels.

Exhibit 1: Employee Turnover

Source: 2013-2016 Crowe Horwath LLP Financial Institutions Compensation and Benefits Surveys

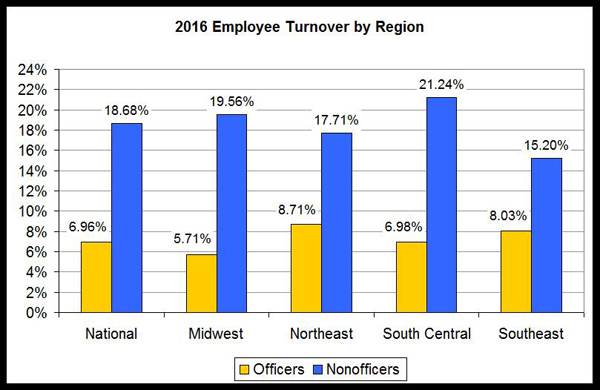

Survey results often vary significantly by region or by state, reflecting local or regional variations in general business trends and the availability of viable candidates for available positions. In this case, however, the regional variations in participants’ responses are relatively modest, as shown in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Employee Turnover by Region

Source: 2013-2016 Crowe Horwath LLP Financial Institutions Compensation and Benefits Surveys.

Nonofficer turnover rates were somewhat higher in the Midwest and South Central regions, and officer turnover was slightly higher in the Northeast. But despite these minor regional variations, the overriding trend in the 2016 survey was consistent, with turnover rates rising over previous years in all regions.

Note that rising turnover rates are not limited to the banking industry. They are part of a broader national trend. Other research shows that employees in many industries are becoming less cautious and more willing to seek out new opportunities as the economy grows.

For example, WorldatWork, a leading member association for human resource professionals, reports a comparable trend is being felt in the retail industry. The association cited a survey by the Hay Group division of Korn Ferry, which found the 2016 turnover rate for hourly store employees reaching a remarkable 65%.1

Obviously, retail clerks and bank tellers are not directly comparable positions. Nevertheless, recruiters in both industries often compete within the same talent pool when filling customer-facing positions—and the competition clearly is intensifying.

WorldatWork also recently reported the results of a 2016 study that included 441 U.S.-based organizations in various industries. In that survey, conducted by the Willis Towers Watson consulting organization, three out of every 10 U.S. employees who responded said they were likely to leave their current employer within the next two years.2

Hidden costs of employee turnover

Turnover rate is one of the most basic and widely recognized human resource metrics, but it takes on even greater significance when it is evaluated in conjunction with separation cost. While knowing how many people are leaving the organization and from which areas is important, it’s often more important to know what those separations are costing the organization.

The average cost of separation for an employee often is estimated to be at least six months’ equivalent of revenue per employee. The 2016 Crowe survey takes a more detailed approach.

Instead of estimating based on six months of revenue per employee, the overall average net income per full-time equivalent (FTE) employee, which was calculated to be $39,182, is measured. Using this more focused formula, the average cost of employee turnover would be $19,951 in lost net income for each employee who leaves.

Another popular rule of thumb puts the cost of turnover at roughly 150% of that particular employee’s annual compensation, and even higher (200% to 250%) for managerial and sales positions. This metric is cited by William G. Bliss, author of one of the most widely cited articles on the topic of turnover costs.3

Bliss’ article presents a comprehensive checklist of items companies should include when calculating the cost of turnover. His approach includes formulas for estimating various costs in six categories:

1. Costs due to a person leaving, including temporary replacements; overtime pay for fill-in staff; exit interviews; any severance pay; and the costs of continuation of employee benefits.

2. Recruitment costs, including advertising, recruiters, pre-employment tests and screening, and other related expenses.

3. Training costs, including general orientation costs; training materials; trainers;, and the cost of time spent by supervisors and coworkers in bringing the new employee up to speed.

4. Lost productivity costs, including estimating the diminished performance during a replacement employee’s first 13 to 20 weeks.

5. New hire costs, including administrative costs of onboarding the new employee such as adding to payroll; setting up necessary identification documents; and establishing computer accounts and passwords.

6. Costs of lost sales, based on either the expected direct sales revenue by position, or average revenue per employee.

Naturally these cost estimates will vary depending on the position being filled and the organizational structure and general business strategy of the bank. However, the checklist does help provide some perspective on how the costs of employee turnover are not always immediately obvious.

Focusing on a major retail bank

Additional recent research by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) Foundation provides added insight that is specific to the banking industry.

The foundation recently funded a study of the consequences of employee turnover on the financial performance of bank branches. The study was conducted across 524 branches within a large regional bank located in the United States.

As you might expect, the results show employee and manager turnover produce an immediate negative effect on branch performance.

But more interesting are the lingering effects of turnover.

The SHRM study found the recovery rate for an employee turnover event is approximately ten months, meaning that it will take the average branch ten months to recover to pre-turnover levels of performance. The recovery time for a manager turnover event is even longer—12 months or more.4

Common causes of high turnover

Regardless of how it’s measured, the cost of employee turnover clearly is significant—which means reducing turnover represents an important cost-saving opportunity.

The first step in developing a strategy to address that opportunity is to understand both the immediate and underlying factors that cause employees to leave—either voluntarily or involuntarily.

Post-separation interviews and surveys are highly valuable tools for gaining insight into those causes, which typically vary according to the duration of an employee’s tenure with the bank.

For example, early turnover—that is, an employee who leaves within the first year of employment—often is attributable to poor selection and employment practices.

For hard-to-fill jobs that require specialized skills and training, management and human resources are sometimes so eager to fill a vacancy that they make an offer to the first candidate who meets the basic qualifications.

Such a rush to judgment can lead to a poor match with someone who is under- or overqualified. Moreover, even if a candidate has the necessary technical skills and experience, management also must consider how well the potential employee will fit with the organization’s culture.

Management’s judgment in this area is likely to be skewed if the bank is hiring out of desperation.

In contrast to early turnover, later turnover—employees who leave after at least one full year of employment—often is attributed to one or more of the following factors:

• Poor relationship with the immediate supervisor.

• Slow promotional opportunities or none at all.

• Less-than-competitive pay increases.

• Limited or nonexistent career and personal development opportunities.

• Inflexibility, or concerns about maintaining work-life balance.

Strategies for reducing turnover

Once the most pertinent contributing factors have been identified, the most effective strategies for reducing turnover will start to become more apparent.

For example, improved recruiting and candidate screening systems can help management avoid a rush to judgment or hiring out of desperation. Likewise, improving management and supervisory skills can help reduce turnover caused by poor supervisor-employee relationships.

Other important elements of an employee retention strategy include a competitive pay structure and advancement opportunities, ideally as part of a total rewards program that encompasses pay, incentives, and benefits, as well as a focus on important cultural and work-life balance concerns.

As management focuses on turnover, the need and relative priorities for such strategies will become more apparent—but that’s not to say they will be easy to carry out.

The design and implementation of effective solutions will take time, effort, and long-term commitment. Nevertheless, as the competition for the best performers continues to intensify, developing consistent and coherent employee retention strategies will become even more important to improving bank performance.

Read Part 1 of series: Talent competition: missed opportunities as battle intensifies

Read Part 3 of series: Employee incentive plans leave room for improvement

1 “U.S. Retail Turnover Rates Highest Since the Great Recession,” WorldatWork online article, Nov. 23, 2016.

2 “Employee Turnover Plagues U.S. Employers,” WorldatWork online article, Sept. 16, 2016.

Tagged under Human Resources, Management, Retail Banking, CSuite, Channels, Community Banking, Feature, Feature3,