Branch angst drives divergent strategies

"Still Crazy After All These Years" sums up ongoing debate

- |

- Written by Melanie Scarborough

Today banking has to be everywhere. But what's the right balance of digital and physical presence?

Today banking has to be everywhere. But what's the right balance of digital and physical presence?

Reports of branch closings by Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, et al don’t generate all that much attention anymore. A hundred shuttered here, 200 there, and even 300 and up—what’s the surprise? Because of acquisitions and spurts of organic, pre-crisis branch binging, these giants were, and probably still are, over-branched. Even more recent branch-reduction moves by big regionals are pretty much along the same line.

But when Umpqua Bank—a long-time and vocal proponent of branches as a strategic weapon—changes direction, that’s a signal that the long-running branch debate has entered a new phase.

The $25 billion-assets West Coast regional, headquartered in Roseburg, Ore., still has more than 300 locations in five states after recently closing about 35 branches. But the mojo has shifted.

Ray Davis, the bank’s former CEO who is now chairman of Umpqua Holdings, says the decision to close branches wasn’t about money; the branches were profitable. “With us, it’s predominantly about customer preferences—they’re moving to online and digital banking—so that the branch lost its importance in some communities,” Davis says.

In areas where Umpqua had several branches and lobby traffic had decreased, it made sense to concentrate the bank’s presence into fewer locations. “We try not to close branches; we try to consolidate them,” Davis says. “We haven’t left markets.”

The present challenge for banks is dealing with customer preferences while also differentiating themselves, Davis says. Twenty years ago, Umpqua differentiated itself by turning branches into “bank stores” that provide a computer café, Umpqua’s custom-blend coffee, and meeting space for groups, such as book clubs and yoga classes—along with banking services. Davis drove the change, which was highly successful and spawned many imitators.

“Now, we have to figure out how to differentiate ourselves with technology coming at us so fast,” Davis says. Umpqua Bank plans to do that primarily through Pivotus Ventures, a subsidiary of Umpqua Holdings charged with creating new technologies and digital models to transform banking. “We’re taking digital platforms to a level that does not yet exist,” he says.

For the branch crowd, that’s a bummer. It’s like Mario Andretti driving a Toyota Prius. But hold on. The change of view of one banker—admittedly a creative genius when it comes to branches—does not tell the whole story.

As some doors close, others open

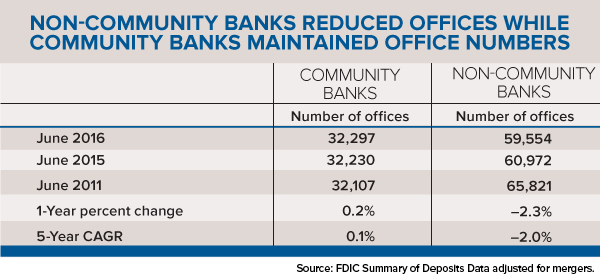

Without question, overall branch numbers are shrinking. According to the FDIC, there were 80,227 bank branches at year-end 2016, down from 94,725 in 2014.

Yet while large banks prune their branches, community banks sprout new ones. Robert Meara, senior analyst, banking group, at Boston-based Celent, says that distinction reflects the separate dilemmas large and small banks face. Banks that built branches on every corner before online and mobile banking became prevalent now have to shed real estate, while smaller banks that want to expand have few options but to add more. “If you have only three branches and want to move into the town next door, what else do you do?” Meara asks.

Complicating the issue is that consumers operate with a fundamental contradiction: While they may visit a branch only a few times a year, they want one available when they need it. Ed Barry, CEO of $960 million-assets Capital Bank, Rockville, Md., likens the phenomenon to condominium shoppers who want a building that has a pool and a gym although they may rarely use either. “That’s what’s happening with branches,” he says. “Customers want to know it’s there even though they may not go in but two or three times a year.”

Everyone seems to agree that today’s branches will continue to be replaced by smaller facilities that are more thinly staffed and highly automated. How to make that transition while keeping the facilities relevant and profitable, however, remains a matter of debate.

Selective expansion

First Financial Bank, an $8.5 billion-assets institution based in Cincinnati, has both opened and closed branches in the past few years, from a peak of 150 in 2009 to 103 present locations. Several factors weigh into those decisions, says President and Chief Banking Officer Tony Stollings. “For existing locations, we’re always monitoring transaction volumes and customer preferences—and profitability comes into play,” he says. The bank has added about ten branches since 2014 as new markets emerged allowing “a strategic fill-in of our existing footprint.”

In 2015, First Financial announced it was going to close three branches in the Dayton market and open about three others there. “Those [moves] are primarily about getting into better growth areas,” Stollings explains. “Sometimes, it’s because of simple things like moving from a location that can be hard to get in and out of. Sometimes, it’s merely a consolidation in a better location around an existing presence that we have. Typically, we’re moving into some place that gives us more opportunity to create the brand presence we’ve invested in.”

As Meara noted, adding branches remains the main vehicle for expansion for smaller banks. Capital Bank recently opened a branch in nearby Columbia, Md., to establish physical presence in an area where it already had a sales team. “It used to be, ‘If you build it, they will come,’” Barry says. “Now, it’s ‘Show me the money.’ Our view is that the role of the branch has been changing and has been in somewhat of a decline in the past decade, but there’s still a relevancy to customers. So we put branches in high-traffic and visibility areas to announce that we’re there.”

Capital Bank’s strategy is to expand its footprint, not to become denser in its present markets. “I definitely need more locations just to have a physical presence in the marketplace,” Barry says. “But we’re more likely to open a branch in Northern Virginia than in Montgomery County [where the bank is based].”

Split over face-to-face

Indeed, as customers visit branches less often, proximity becomes less of an issue. Dave Martin, founder of bankmechanics and a former retail bank executive, explains it in terms of shopping circles. People generally shop in a grocery store close to home because they buy groceries several times a week; they will drive farther to buy clothes because those purchases are less frequent. “So as the need for visits to a bank branch is reduced, the willingness to shop a bigger circle grows,” he says. “Historically, the more branches you had, the more convenient of a bank you were. But if you need a bank branch only four or five times a year, spending ten minutes to get to it is not a big deal.”

Martin says even people who rarely come into the bank want to know they can speak face-to-face with someone if they have a problem. “People don’t visit a branch; they want to visit a banker,” he says. “So if you argue that branches will go away, you’re arguing that people will never value face-to-face contact.” It’s primal, Martin adds, to want to know the person to whom you’ve entrusted your assets.

Most analysts agree, but not all. Margaret Kane, CEO and founder of Kane Bank Services in Sacramento, predicts that branches of the future will target specialized markets, such as commercial real estate and, in the short term, financial advisement, but she doesn’t see the advice-led model as viable for the long term.

“If you look at the investment space, bankers have been saying that customers will still need to come in and see someone for advice,” Kane says. “That’s proving to be less true because there are a lot of platforms that allow you to do that online.” She says her 23-year-old daughter manages her finances online and “is never going to go into a branch for advice. The idea that people will still need branches for advice is going to fundamentally change.”

Umpqua Holdings’ Davis points to another challenge. “Most people say they see banks evolving into advice-driven facilities,” he says, “but if that happens, the big problem is you still have to get people to go in.” It used to be people had to come in to cash a check or make a deposit. Now, bankers will have to be more creative to bring people in, he says.

How do you draw in tech-savvy millennials? Kevin Tynan, senior vice-president for marketing at Chicago-based Liberty Bank for Savings, with assets of $820 million, says that some young people who now bank online will always bank online. “But to look at millennials now and say that’s the way they’re going to be when they’re 55 is erroneous,” he says. “After 50, they may be interested in where they can get the highest interest rate and the best service, and want to have someone down the street they can talk to. Experience colors preferences, and there will be an evolvement of the customer.”

Next steps

Tynan may be correct, but Ken Olan, CEO and founder of CAKE Performance Group, Houston, offers a different take. Any smart bank, he says, is looking at demographics and psychographics to determine if and where to build branches.

Olan says the placement and design of future bank branches will depend on the bank’s priority. “Banks that have a heavier commercial business will probably continue to use branches. In the long term, more consumer banking—if not the vast majority—will be electronic.” He foresees branches no larger than 700 square feet, equipped with interactive video and staffed by one or two people.

“We will continue to see branches because they help dominate market share, but we’ll most likely see them develop into smaller locations manned by universal bankers who can do a lot more,” Olan says. His firm developed online training to help branch employees broaden their skill set.

Capital Bank’s new branches are “not the typical branch of 20 years ago,” says Barry. They have smaller square footage and are more thinly staffed, “but more tightly integrated with our sales team.The branch becomes that first level of help desk in customer support.”

Celent’s Meara says plans for future branches have common technological elements, but broad variations in design. “Where everyone seems to be in agreement is that branches are going to be smaller, more highly automated, with more assisted self-service options—like the self-checkout at the grocery store,” Meara says. “They will be staffed by more highly trained and compensated universal bankers, and designed more for sales and service than for transactions.”

However, he predicts those changes will come gradually because the process is so complex. “Banks have chased the bright, shiny object of mobile banking—responding appropriately to that imperative—but because the branch challenge is messy and expensive, they haven’t made as much progress,” Meara says. “Everyone loves the idea of generalized self-service, but how do you provide that? With a teller? After hours? With video? Why do you think customers will want to drive to a branch to interact with video?”

“Lots of these topics are polarizing,” says Meara, “and there are still relatively few institutions that have tangible experience with new operating devices.”

Tynan says there’s a bigger problem. In his view, some of the new techno-offices are just “selling booths,” and customers are leery of the sales culture. “We open automated branches and they can’t solve problems, which is what customers say they want,” he says. “The focus is on reducing transactional cost instead of improving customer experience.”

Tynan points to Amazon and Apple earning the top ranks in consumer trust while banks lag in eighth place. “Bankers use technology to reduce transaction costs; retailers use technology to improve customer service,” he says. “We’re not likely to change the perception of banks if we keep opening automated, techno-offices.”

For Tynan, the ideal branch of the future would be a coffee-shop model staffed by one or two people, but with no ATMs or automated deposit machines—“an office where someone can come in and get service with no overtones of selling. That would demonstrate that we’re not in it totally to sell you more and more products.”

Physical, digital blend

Banks do have to consider their bottom lines, and technology can reduce costs without diminishing customer service.

“Certainly, migrating transactions to self-service is key because one of the largest expenses in the branch is labor,” says Bob Gibson, vice-president of branch operations at Cummins Allison, which offers cost-saving tools for customer self-service and back-office employees. In the back office, banks can save money with technology that enables them to “insource”—for instance, recycling cash deposits to stock the branch’s ATM instead of paying for daily armored truck transport. Or self-service coin handling machines that help banks cut costs and attract customers.

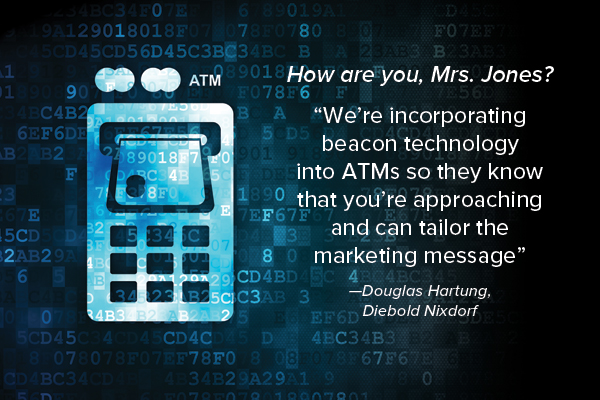

Douglas Hartung, senior director, software innovation, at Diebold Nixdorf, says the company is working on facial and voice recognition tools to benefit banks and customers. “Different types of biometrics will be appropriate for different types of uses,” he says. “ATMs could be enabled through a server to activate facial recognition on the customer’s phone. Biometrics are advancing so rapidly that it would be expensive for banks to keep upgrading their ATMs, so why not use the device in everyone’s pocket that already supports biometrics?”

As an example of the increasing interconnection of digital technology and physical delivery channels, Diebold Nixdorf wants to enhance utilization of mobile devices with self-service terminals, in a branch or elsewhere—for example, using beacons and location-based services at the ATM. “Right now, the ATM doesn’t know it’s dealing with you until you insert your card and type in your PIN,” Hartung explains. “We’re incorporating beacon technology into ATMs so they know you’re approaching before you get there and can tailor the marketing message.”

The same technology could be set up for customers coming into a branch.

Plan to survive, thrive

Cost-saving technology, strategic branch distribution, customer service, and customer preference will help branches survive for the foreseeable future—whether they thrive is up to them.

“Branches can either be the primary growth engines of your institution or albatrosses that weigh down your organization’s profitability,” bankmechanics’ Martin says. “If your branches haven’t been spruced up in years and look desolate, if they look like they’re withering on the vine, they become an albatross because they look dated.”

Also keep in mind, Martin says, that as customers visit your branches less often, the quality of those visits counts more. “Now that you see them only four or five times a year,” he says, “if they have a bad experience, you’re in trouble.”

Banks considering closing branches must factor in CRA requirements. At First Financial Bank, Stollings says, “When we think about strategic locations, we are very purposeful around our community development activities and want to be sure we serve appropriately the low-income markets. Right now, across our 103 locations, 23% to 25% are located in low- to moderate-income census tracts.”

When weighing the value of tellers versus automation, banks also should consider security. Olan points out that when transactions like account openings are conducted in the branch, it adds to the comfort level of both customers and banks. “The customer can come in and talk to someone they expect to be knowledgeable,” he says, “and because the bank can look that person in the eye, fraud risks are diminished.”

Still, Kane recommends, “Banks should be relentlessly focused on getting the online experience right. Banks that survive will be those that have the best online experience.”

Yet no matter how attractive or technologically advanced they are, branches will be a detriment unless they have a specific role tied to the bank’s business strategy, says Barry of Capital Bank. “If you get [branch distribution] right, it can be a real advantage. If you miss the mark, it’s a ton of capital deployed with dubious payback,” he says. “We’re seeing a lot of people trying to figure out physical and virtual distribution, and where do those strategies converge.”

Martin hazards a guess: The future “is going to be high tech, but it’s going to continue to be high touch. There are likely to be fewer branches, but they’ll continue to be the center of the banking universe. Both things can be true."